I must admit to having reserved a certain amount of judgment on just how much I liked Sailing to Sarantium, the first book of Guy Gavriel Kay's Sarantine Mosaic diptych, until I saw how the story ended in this second volume, Lord of Emperors,

because the first book didn't quite feel like it could stand on its

own. The two really should just be published in an omnibus edition and

be done with it, to make sure that nobody who was left a little meh at

the end of the first book would miss out on the absolute joy to be had

in the second.

As I observed before, the story told

here is to a vast degree a slightly fantastical retelling of the reign

of Justinian and Theodora of Byzantium, with some nifty artisanal

viewpoint characters to give it life and color and emotional oomph.

But

here in the second volume, the story at last decides to diverge from

that most glorious of Byzantine periods, even as it brings more

similarities to that story to the fore; thus a semi-barbarian queen,

Gisel, who had a scene in the first book is more fully fleshed-out and

revealed to be a fantasy (and younger and prettier and unattached)

version of Amalasuntha of the Ostragoths, whose mistreatment at the

hands of usurpers gave Justinian an excuse to reunite the Western and

Eastern Roman empires.

Preparations for that great

event, or rather, its fantasy equivalent, serve as the backdrop for this

second volume of the diptych, for our hero of the first volume, Crispin

the Rhodian mosaicist, brought tidings from Gisel to Valerius II (aka

Justinian) and so can be said to have touched off Valerius' Great

Excuse. Thus while Crispin busily works on decorating the great dome of

the Sanctuary to Jad (aka the Hagia Sophia), plots unfold all over the

place. But wait, there is more.

Lord of Emperors

brings two new and important, and deeply interesting, characters into

the mix, characters who do more, really, to drive the novel's plot than

even Crispin or Valerius or Gisel. The first is a Bassanid (Sassanid)

doctor, Rustem, unexpectedly come to prominence in his own country and

then sent by his king to (cough) learn things in Sarantium; the second

is Cleander, the hotheaded teenaged son of Sarantium's Master of the

Senate, who makes all the messes that Rustem winds up having to clean

up. Messes which wind up involving all of the characters, high and low,

from the first novel, and keep things entertaining, but still wind up

just being distractions to the MAJOR PLOT of the mighty that is the most

dramatic, but also troublesome, element of the two novels.

I

say troublesome because, just as the novels' story diverges

dramatically from actual history and seems poised to be exploring some

really tantalizing "what ifs" that I'm trying desperately not to spoil

for you except to say that yes, they involve the novel's Belisarius

counterpart, Leontes, quite intimately, which is part of what makes

these what ifs so very tantalizing to contemplate, it then briskly winds

down. The effect is kind of like if, say, Harry Turtledove had written

his alternate U.S. Civil War stories but then just stopped right after

the South won. Frustrating.

But forgiveable, here, only

because everything else is so beautiful. Rustem is a lovely addition to

the cast of characters and his story is as moving as Crispin's, as

Valerius', as Alixiana's, as those of the chariot racing superstars and

faction dancers and cooks (and cook's assistants) we already had met.

Cleander spends a lot of the novel as the jerk you want to slap, but

he's perhaps the one who undergoes the most character development; you

don't exactly wind up cheering for him, but in the end you wind up

pretty glad he's there.

As I've come to expect from

Kay, there are some heartbreakingly emotional moments, some lovely

prose, and, yes, some overemphasis of some things (like repeatedly

pointing out how subtle everyone is). I really, really hope there's

another volume of this some day, though. I want to know what happens

now, since history doesn't tell me.

One other thing

of note: beautifully, Kay also manages to leave us the idea that our

man Crispin is the novel counterpart to the unknown artisan who made the

wonderful Justinian and Theodora mosaics in the Basilica of San Vitale

in Ravenna:

Which

is a lovely grace note to a work of art that really didn't need any

more, but that's why they're grace notes. I mean, look at those things.

If these books don't tell their creator's story, they tell a story that

might have been his. And they tell it beautifully.

*The

historical detective work of looking for the historical figures who

might have inspired the regal characters in these books is deeply

unnecessary for enjoying them, but it's lots of fun if you're a certain

kind of person.

Kate Sherrod blogs in prose! Absolutely partial opinions on films, books, television, comics and games that catch my attention. May be timely and current, may not. Ware spoilers.

Sunday, April 26, 2015

Guy Gavriel Kay's LORD OF EMPERORS

Friday, April 17, 2015

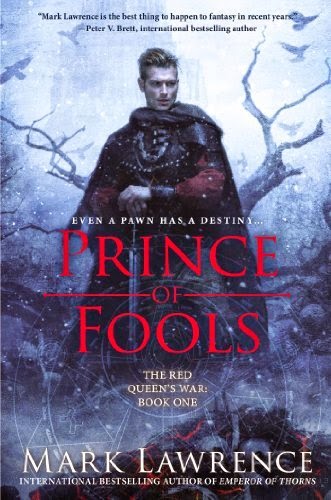

Mark Lawrence's PRINCE OF FOOLS

I absolutely loved Mark Lawrence's Broken Empire trilogy, so there was no way I was not going to dive right into this sidequel pretty damned soon. The world created around the story of Jorg Ancrath begs to be further explored, and Lawrence is a master at creating unique character-narrators to lead one's expeditions. So I had very high expectations heading into Prince of Fools, first of a new series titled The Red Queen's War.

They weren't entirely met, but I didn't really notice that as I was reading, because my expectations were beside the point. Lawrence was revisiting his world but doing so in a completely different way from what I'd come to expect, and doing it brilliantly. So Prince of Fools, for all its familiar settings and cameo appearances by characters from the other books, is very much its own thing, and its sort-of-hero, Prince Jalal Kenreth, is very much his own man. Well, at least as much as Jorg was. I mean, look how problematic Jorg turned out to be!

Jalal, or Jal as he wishes people would not call him, is also problematic, but not quite so much so as was Jorg. Jalal is relatively simple (or at least seems so, so far): he is a self-professed and unapologetic coward, and tells us so clearly and distinctly every few pages. He's proud of what a good coward he is, very good at making fun of what a really almost perfect coward he is, and very entertaining and droll on the general subject of his mastery of the finer points of cowarding.

Except, of course, he isn't. Because one thing that he never seems to have noticed about actual cowards is that they never admit to being cowards. Far from it. They always have very high-flown, high-horse riding reasons for their actions that are actually quite noble and brave and necessary, thank you very much. And if you use the C word in their presence, they might just slap you with a glove and demand you meet them on the field of honor. At which they'll not show up because they had some highfalutin' duty to perform. Yeah, that's it.

No, Jal is really pretty much a hero, but doesn't want that to become known, because then people will expect things of him. Jal, can you rescue this maiden, Jal, can you solve this dilemma, Jal can you fend off this invading army that threatens our very existence, Jal can you marry this homely but rich maiden for the good of the Realm. If there's anything he fears, it's that. Far more pleasant to drink and gamble and whore around, leap from noble bedchamber window to noble bedchamber window to have a go at the sister, etc.

Until plot things happen that bind him magically to a by-gods Viking whose very involved backstory has left him a prisoner of Prince Jal's grandmother, the Red Queen. Said Viking due to be released until Jal gets a load of his overwhelming brawniness and diverts him into the fighting pits instead so that Jal can make some money off him. And then magic.

The tale thus becomes a different kind of road narrative from that we enjoyed with Jorg and his Brotherhood. Jal and Snorri (well, of course the Viking is named Snorri. Read your sagas!) must travel north to do battle with evil forces that have destroyed Snorri's family and realm, forces that he at first just thinks are rival Viking bands but turn out to be closely related to the Big Evil that so warped Jorg's tale and against whom Jal's grandmother and her eerie and witchy Silent Sister are subtly arrayed.

The resulting book is a bit less complex than the Broken Empire books (or at least seems so thus far!), a bit less uncomfortable to enjoy, but compensates for all this by being a lot more fun. Snorri is a hilarious hero straight out of the sagas (he'd sweep all the categories except maybe Outlawry if the guys at the Saga Thing podcast were for some reason to take on this story), whose many notable witticisms manage to keep things amusing even when Jal stops cracking wise as narrator. Their story and the weird magic that binds them is compelling and occasionally hair-raising. There were plenty of undead/necromancy encounters in the Broken Empire books, but the walking dead in Prince of Fools are much scarier, even if they do maybe owe a lot to A Song of Ice & Fire's White Walkers. Or do they?

This is how you do a sidequel, kids. Now I'm seven kinds of psyched for the sequel to the sidequel. Sesidequel? Sedequel?

They weren't entirely met, but I didn't really notice that as I was reading, because my expectations were beside the point. Lawrence was revisiting his world but doing so in a completely different way from what I'd come to expect, and doing it brilliantly. So Prince of Fools, for all its familiar settings and cameo appearances by characters from the other books, is very much its own thing, and its sort-of-hero, Prince Jalal Kenreth, is very much his own man. Well, at least as much as Jorg was. I mean, look how problematic Jorg turned out to be!

Jalal, or Jal as he wishes people would not call him, is also problematic, but not quite so much so as was Jorg. Jalal is relatively simple (or at least seems so, so far): he is a self-professed and unapologetic coward, and tells us so clearly and distinctly every few pages. He's proud of what a good coward he is, very good at making fun of what a really almost perfect coward he is, and very entertaining and droll on the general subject of his mastery of the finer points of cowarding.

Except, of course, he isn't. Because one thing that he never seems to have noticed about actual cowards is that they never admit to being cowards. Far from it. They always have very high-flown, high-horse riding reasons for their actions that are actually quite noble and brave and necessary, thank you very much. And if you use the C word in their presence, they might just slap you with a glove and demand you meet them on the field of honor. At which they'll not show up because they had some highfalutin' duty to perform. Yeah, that's it.

No, Jal is really pretty much a hero, but doesn't want that to become known, because then people will expect things of him. Jal, can you rescue this maiden, Jal, can you solve this dilemma, Jal can you fend off this invading army that threatens our very existence, Jal can you marry this homely but rich maiden for the good of the Realm. If there's anything he fears, it's that. Far more pleasant to drink and gamble and whore around, leap from noble bedchamber window to noble bedchamber window to have a go at the sister, etc.

Until plot things happen that bind him magically to a by-gods Viking whose very involved backstory has left him a prisoner of Prince Jal's grandmother, the Red Queen. Said Viking due to be released until Jal gets a load of his overwhelming brawniness and diverts him into the fighting pits instead so that Jal can make some money off him. And then magic.

The tale thus becomes a different kind of road narrative from that we enjoyed with Jorg and his Brotherhood. Jal and Snorri (well, of course the Viking is named Snorri. Read your sagas!) must travel north to do battle with evil forces that have destroyed Snorri's family and realm, forces that he at first just thinks are rival Viking bands but turn out to be closely related to the Big Evil that so warped Jorg's tale and against whom Jal's grandmother and her eerie and witchy Silent Sister are subtly arrayed.

The resulting book is a bit less complex than the Broken Empire books (or at least seems so thus far!), a bit less uncomfortable to enjoy, but compensates for all this by being a lot more fun. Snorri is a hilarious hero straight out of the sagas (he'd sweep all the categories except maybe Outlawry if the guys at the Saga Thing podcast were for some reason to take on this story), whose many notable witticisms manage to keep things amusing even when Jal stops cracking wise as narrator. Their story and the weird magic that binds them is compelling and occasionally hair-raising. There were plenty of undead/necromancy encounters in the Broken Empire books, but the walking dead in Prince of Fools are much scarier, even if they do maybe owe a lot to A Song of Ice & Fire's White Walkers. Or do they?

This is how you do a sidequel, kids. Now I'm seven kinds of psyched for the sequel to the sidequel. Sesidequel? Sedequel?

Sunday, April 5, 2015

Guy Gavriel Kay's SAILING TO SARANTIUM

There

is a lot of attention to and respect for craft in Canadian fantasist

Guy Gavriel Kay's fiction, and not just as a source of metaphor, though

the tapestries of Fionavar and, here, the mosaics of the

pseudo-Byzantine Sarantine empire, certainly serve as highly effective

over-arching ones for the story structures he's created.

There were, though, no weavers in Fionavar. The tapestry was woven by a god, though not one of the gods who romped and fought and occasionally fornicated in the land -- they had personalities and desires and whims. The Weaver of Fionavar was much more impersonal, not a character.

But in Sailing to Sarantium, while yes, the overall story can be seen as a mosaic created by a divine mosaicist, there is also a real and earthly artisan who is a master of that art, and his story is the main one of this first novel in the Sarantine diptych.

Said artisan is one Crispin, who begins the novel far from the fabled city of Sarantium. Crispin is a Rhodian -- a citizen of this world's western Roman empire after it was sacked by this world's Visigoth analogues* -- and a mosaicist of considerable skill and dedication, if not yet reputation. The reputation is all his partner's, and it is his partner who is invite-commanded by the emperor to come to Sarantium and work on the novel's Hagia Sophia analogue. The partner,though, is old, and tired, and Crispin is merely middle-aged and embittered, so they decide it is he who will go "Sailing to Sarantium" in the novel's idiom for finally getting a shot at the big time, though because the imperial courier dawdled with the message it's too late in the year for safe sailing and so Crispin must travel overland.

So far this sounds about as fantastic as a Lars Brownworth podcast**, and I will just spill the non-fantastical beans here and say that, well, a Clark Ashton Smith story this is not. There is very little magic here, and not much in the way of mythical creatures either -- about as much as you'd see in, say, four or five chapters of A Song of Ice and Fire. But like those books, you're not going to be reading this for the dragons and centaurs and necromancers. You'll read it for the characters and the intricate and crazy court politics and for Crispin's story, the story of an artisan, the kind of guy we can never know any real story about (hence, I posit, the decision to make of this tale a fantasy instead of just a historical novel set in Byzantium. At least in part.) because artisans' names and biographical details did not make the history books until, overall, the Renaissance.

And also because, so far in my experience at least, when Kay writes fantasy, he's interested in exploring one of the more interesting possibilities that the fantasy genre offers: that of examining a world in which religion and its attendant rituals are not matters of mere faith/belief, as they are in our world, but matters of fact. Gods exist and prove their existence by directly interacting with humans (sometimes quite intimately). Ignoring them, to paraphrase Philip K. Dick, does not make them go away. And neglecting to propitiate them has real and tangible consequences that can't be argued about (or at least not much). We saw this in spades in Fionavar; here it's all a bit more subtle. There are pagans still in the Sarantine world, and we get at least one spectacular encounter with the reality of their pantheon and program during Crispin's journey to the great city from the sticks, but there is also a monotheism where, at least in this first novel, no proof is offered. It's all more like ours. It's all about belief.

Which lets Kay explore at one remove the schism between Western and Eastern Christianity that was just really developing in Byzantiume during Justinian's reign. The official religion of the Sarantine empire has sort-of-pagan trappings in that its single deity, Jad, is a sun god, but, just as Christianity was through its history, there's monotheism and there's monotheism. Pagan tugs at believers' heartstrings have some venerating a pantheon of martyrs almost as deeply as the god, and many arguing over whether the deity's incarnated earthly son was or was not as divine as the god itself.

All of this may turn off some readers, but those who have the patience for it are amply rewarded. The theological nitpicking deeply informs some of Crispin's very real and intense experiences, and his plans and visions for his coming triumph, the decoration of the pseudo-Hagia Sophia, which is to be more than a little bit of an assertion of doctrine given form in stone and mortar and prismatically lovely glass tesserae.

As I said, Kay loves exploring craft, and takes it as seriously as fodder for stories as he does his own practice. The care of Crispin for not merely design but construction and composition mirrors Kay's own attention to his craft. The result is as splendid as the dome of Hagia Sophia must have been in Justinian's day.

All this and some crazy action, too. Chariot races! Chariot crashes! Fighting! Sometimes in a bathhouse! And intrigue. So much intrigue. Crispin's arrival upsets many, many applecarts.

A caveat, though; as others have complained, Sailing to Sarantium ends feeling incomplete. Very little is resolved; most is saved for the second volume Lord of Emperors (which I'm already reading, of course). If you're going to read this, then, do yourself a favor and make sure you have the second book ready at hand.

Go, Blues!

*And let's just get this all out of the way and say that, fantasy trappings aside, this novel is basically set in Byzantium in the reign of Justinian and Theodora. All the events of that period are mirrored here, from the Nika riots and Theodora's famous quote about how imperial purple is a good color in which to be buried to the near-eternal conflict between the Blue and Green factions that are really only nominally about the two major colors striving for supremacy in the chariot racing marvel of the Hippodrome (as in the real Byzantium, the two factions also correspond to sides in a religious schism), to the need, after said riots, to rebuild the city and especially its primary religious edifice. It's all so on the nose, but as Byzantium is woefully under-represented in fiction, I happily allow it.

**If you've not listened to the marvelous Twelve Byzantine Rulers, go! Listen! It's glorious! I promise!

There were, though, no weavers in Fionavar. The tapestry was woven by a god, though not one of the gods who romped and fought and occasionally fornicated in the land -- they had personalities and desires and whims. The Weaver of Fionavar was much more impersonal, not a character.

But in Sailing to Sarantium, while yes, the overall story can be seen as a mosaic created by a divine mosaicist, there is also a real and earthly artisan who is a master of that art, and his story is the main one of this first novel in the Sarantine diptych.

Said artisan is one Crispin, who begins the novel far from the fabled city of Sarantium. Crispin is a Rhodian -- a citizen of this world's western Roman empire after it was sacked by this world's Visigoth analogues* -- and a mosaicist of considerable skill and dedication, if not yet reputation. The reputation is all his partner's, and it is his partner who is invite-commanded by the emperor to come to Sarantium and work on the novel's Hagia Sophia analogue. The partner,though, is old, and tired, and Crispin is merely middle-aged and embittered, so they decide it is he who will go "Sailing to Sarantium" in the novel's idiom for finally getting a shot at the big time, though because the imperial courier dawdled with the message it's too late in the year for safe sailing and so Crispin must travel overland.

So far this sounds about as fantastic as a Lars Brownworth podcast**, and I will just spill the non-fantastical beans here and say that, well, a Clark Ashton Smith story this is not. There is very little magic here, and not much in the way of mythical creatures either -- about as much as you'd see in, say, four or five chapters of A Song of Ice and Fire. But like those books, you're not going to be reading this for the dragons and centaurs and necromancers. You'll read it for the characters and the intricate and crazy court politics and for Crispin's story, the story of an artisan, the kind of guy we can never know any real story about (hence, I posit, the decision to make of this tale a fantasy instead of just a historical novel set in Byzantium. At least in part.) because artisans' names and biographical details did not make the history books until, overall, the Renaissance.

And also because, so far in my experience at least, when Kay writes fantasy, he's interested in exploring one of the more interesting possibilities that the fantasy genre offers: that of examining a world in which religion and its attendant rituals are not matters of mere faith/belief, as they are in our world, but matters of fact. Gods exist and prove their existence by directly interacting with humans (sometimes quite intimately). Ignoring them, to paraphrase Philip K. Dick, does not make them go away. And neglecting to propitiate them has real and tangible consequences that can't be argued about (or at least not much). We saw this in spades in Fionavar; here it's all a bit more subtle. There are pagans still in the Sarantine world, and we get at least one spectacular encounter with the reality of their pantheon and program during Crispin's journey to the great city from the sticks, but there is also a monotheism where, at least in this first novel, no proof is offered. It's all more like ours. It's all about belief.

Which lets Kay explore at one remove the schism between Western and Eastern Christianity that was just really developing in Byzantiume during Justinian's reign. The official religion of the Sarantine empire has sort-of-pagan trappings in that its single deity, Jad, is a sun god, but, just as Christianity was through its history, there's monotheism and there's monotheism. Pagan tugs at believers' heartstrings have some venerating a pantheon of martyrs almost as deeply as the god, and many arguing over whether the deity's incarnated earthly son was or was not as divine as the god itself.

All of this may turn off some readers, but those who have the patience for it are amply rewarded. The theological nitpicking deeply informs some of Crispin's very real and intense experiences, and his plans and visions for his coming triumph, the decoration of the pseudo-Hagia Sophia, which is to be more than a little bit of an assertion of doctrine given form in stone and mortar and prismatically lovely glass tesserae.

As I said, Kay loves exploring craft, and takes it as seriously as fodder for stories as he does his own practice. The care of Crispin for not merely design but construction and composition mirrors Kay's own attention to his craft. The result is as splendid as the dome of Hagia Sophia must have been in Justinian's day.

All this and some crazy action, too. Chariot races! Chariot crashes! Fighting! Sometimes in a bathhouse! And intrigue. So much intrigue. Crispin's arrival upsets many, many applecarts.

A caveat, though; as others have complained, Sailing to Sarantium ends feeling incomplete. Very little is resolved; most is saved for the second volume Lord of Emperors (which I'm already reading, of course). If you're going to read this, then, do yourself a favor and make sure you have the second book ready at hand.

Go, Blues!

*And let's just get this all out of the way and say that, fantasy trappings aside, this novel is basically set in Byzantium in the reign of Justinian and Theodora. All the events of that period are mirrored here, from the Nika riots and Theodora's famous quote about how imperial purple is a good color in which to be buried to the near-eternal conflict between the Blue and Green factions that are really only nominally about the two major colors striving for supremacy in the chariot racing marvel of the Hippodrome (as in the real Byzantium, the two factions also correspond to sides in a religious schism), to the need, after said riots, to rebuild the city and especially its primary religious edifice. It's all so on the nose, but as Byzantium is woefully under-represented in fiction, I happily allow it.

**If you've not listened to the marvelous Twelve Byzantine Rulers, go! Listen! It's glorious! I promise!

Labels:

ASOIAF,

Byzantium,

fantasy fiction,

Guy Gavriel Kay,

historical fiction

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)