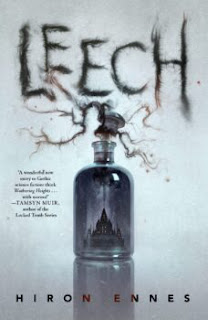

A lot of books I read nowadays feel like video games in prose, and Hiron Ennes' debut novel, Leech is a perfect example of this. It starts with our narrator riding a train through a snowy landscape to a destination that feels very much like the end of the line at the end of the world, and I couldn't stop thinking of that great old classic point and click adventure that was Benoit Sokal's Syberia games.

The world our unnamed protagonist inhabits, though, is somewhat lacking in those games' clockwork charm (aesthetically it's closer cousin is Mark Caro and Jean-Pierre Jeunet's City of Lost Children) though it is heavy on their air of decayed glamor as our protagonist enters a decrepit chateau in the extreme north to take up the post of resident physician amidst a family straight out of the best gothic fiction: a baron, on the brink of death for decades but kept alive by all sorts of gimcrack technology that allows him to, for instance, leave his colon upstairs in his tower bedroom when he joins his household for formal dinners (a memorable moment of maintenance has our protagonist holding "the congested metallic sponge that passes for his spleen" for instance); the baron's feckless and alcoholic son; the son's louche and perpetually pregnant wife; their twin daughters, all but literally joined at the head and possessed of strange paranormal abilities; the capable but mute houseboy who keeps it all running more or less smoothly...

But the chateau's denizens are nowhere near as weird as our multiform (and, for many reasons, delightfully unreliable) narrator, who is quite possibly the most unusual protagonist I've encountered in literature, in that they are a hive mind that parasitically occupies innumerable human bodies scattered throughout what's left of the world.* Calling themselves the Institute, this parasite has taken over the entire health care industry, such as it is in a post-apocalyptic hellscape in which the moon has cracked open and the land is mostly toxic and frozen and inhabited by all kinds of bizarre monsters.

The instance of the Institute who is our narrator, therefore, is constantly** experiencing things their other selves are doing in warm research libraries and cold operating rooms and filthy tenements and down dangerous mine shafts while they sip water at the baron's miserable dinner table and get felt up under that table by the baron's daughter-in-law -- or, as happens quite soon in the narrative, dissect a corpse that used to be one of their selves only to find that what killed that body was another parasite!

Late in the novel, or narrator has questions and insights that really apply to us all:

I don't know if I'm even human, or if I'm only the synthesis of all my infections, if bits and pieces of Pseudomycota and The Institute and every other organism that has colonized me are still fighting in my blood, trying to conquer the territories of my muscles and consciousness. I don't know if I'm only an accumulation of organized cells that has deluded itself into thinking it's something more.

I'm reminded a little of one of my favorite books that I hate (as in it squicks me out every time I read it, but I keep re-reading it because it's so good), the late Greg Bear's Blood Music, in which the somatic cells of a researcher's body become individually sentient and self-aware after he injects himself with a research product in order to steal it. Bear didn't address all the other cells that occupy a human body like, say, gut bacteria, but if he had the result might be something like our narrator and their struggles to understand themselves as the novel's central drama evolves inside them.

Even before the existential dilemmas kick in, Ennes slips in clues here and there, starting very early into the story, suggesting that our narrator's grasp on the situation and even on their own identity is not what it seems, and it's only the least of these that relies on well-known canards about how parasites can manipulate their hosts! There's so much more going on here. So much! And I haven't even talked really about Emile, the aforementioned mute houseboy who is the product of a few centuries of an isolated human population's evolution into what might be a whole new sub-species of gray-skinned human with an apparent resistance to both of the novel's weird invasive organisms! Or about the whole Montish culture from which he comes, with its tradition of shaggy dog stories which... kind of signpost that the reader is in for an ambiguous ending, as fits a tale told by an unreliable narrator...

I am certainly finishing my reading year on a high note, even if nothing else is going all that well. I'm going to try to finish a few more reads before we ring in 2023 (ugh) but if I don't, happy new year. Or something. Watch out for creepy black grassy things in jars.

*And of course, since our protagonist has multiple bodies -- multiple lives -- at their disposal, there is also a potential for respawning, making this story even more video game-like.

**Except when it's not; distance isn't entirely obviated by the Institute's nature. Much like radio signals can't penetrate very far underground and attenuate over vast distances, the Institute's ability to communicate with itself diminishes at inconvenient moments, too.

"I cannot quite understand these fables, not can I discern their use. I suspect they are born from the peculiar, suspect anxiety that there is something fundamentally fragile about humanness. The dead that perhaps, if one takes time to peel back the skin of another, they will find an imposter, a machine, or, stranger still, something like me."

No comments:

Post a Comment

Sorry about the CAPTCHA, guys, but without it I was getting 4-5 comment spams an hour.