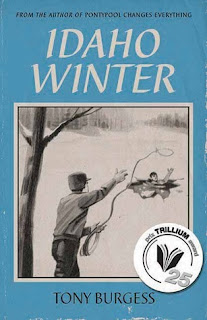

Sooner or later, I was bound to run into a book in which a character within that book not only discovers they are a character in a book, but also manages to have words with their author. It's been a temptingly low hanging fruit since the book tree was planted. Or something like that.

And I'm not surprised to see it in the works of Tony Burgess, whose narrators often address asides to their readers, asides that not only comment on events within the narrative but on literary tropes that are or aren't being employed, the weirdness of writing generally, etc. Ordinarily I roll my eyes at this kind of thing. But of course, this is Tony Burgess, a writer whose works I can't stop compulsively reading and re-reading, even though they horrify me body and soul the way nobody else's can unless it's maybe Jeremy C. Shipp.

Of course Idaho Winter's eponymous hero has a terrible, pitiful existence; he's in a Tony Burgess novel. He's not exactly going to be showered in praise and given everything he could ever want for his birthday and marry his childhood sweetheart and live happily ever after. But where in other novels Idaho (yes, that is his name; moreover, his dad's name is Early, as in Early Winter. But his mother is simply known as Wife. We'll get to that) might encounter language poisoned zombies, or a teeming hellscape in which zombies have been shot into orbit, there to block out the sun in their sheer twitching numbers, here his antagonists are merely everybody who knows him or meets him, and for no reason at all except that Idaho seems to have been Born to be Hated, like the hapless hero of some second-rate Middle Grade novel. Except turned up to 11. So Idaho's father, Early, only ever feeds him half-rotten (or wholly rotten; he's not picky) roadkill and uses Idaho's bedroom as a trash heap; the school crossing guard meticulously plans and maliciously executes Idaho's near-death-by-car every morning, cursing when he manages to escape today's car after she has carefully guided it to hit him at high speed; other students in his class not only treat him with grotesque unkindness but are punished by the teacher if they treat him with insufficient grotesque unkindness, making every day an unofficial competition to see who can be the meanest to Idaho Winter, with maybe an accidental actual school lesson or two.

All of this begins to change when Idaho, on the day we have first encountered the horrors of his daily existence, gets a tiny break from them when he meets a girl named Madison. Madison is so kind and has so much love for the world that she can even extend a little to Idaho, and furthermore not only shares his pain but is very much pained by the fact of his painful existence, and the two form the beginnings of Idaho's first friendship in a series of sweetly tender exchanges that are obviously setting up something horrible to happen to them both. And when it does, Idaho, who is completely alien to the concept of helping others or standing up to danger on another's behalf because there have been no examples of either in his life, runs home.

And things get weird, because Tony Burgess, author of Idaho Winter and of Pontypool Changes Everything and of The N-Body Problem*, informs us that this in no way reflects his intentions for how this scene was supposed to play out. Idaho has gone utterly rogue, off script, and, in the process, discovers that there is an actual author of all of his sorrows and that Tony Burgess is that author, and does what any sensible pre-teen boy who is all but feral and only knows how to lash out in hapless self-defense at best might do. As Burgess explains to him that his existence is so ridiculously and undeservedly horrible on purpose, the better to make his story stand out, Idaho realizes that nothing is real and that he actually has the upper hand in this weird moment.

When Tony Burgess, author of Idaho Winter, finally gets out of the closet in Idaho Winter's terrible house, he emerges into an utterly unrecognizable and bizarre world full of monsters from Idaho's unconscious (my favorite: the Mom-bats, and you'll have to read the novel to find out what those are like) and conscious thoughts and the surface of the earth is uninhabitably dangerous to characters and authors like him. When monsters finally chase him underground, he discovers a small cadre of minor characters from his story, most of whom he hadn't even sketched out beyond giving them names (leading me to of course conclude that his naming of Idaho's mother as simply Wife represents a writer's habit of using stand-in words or names in early drafts until they find the perfect moniker) and the merest beginnings of a role within the town -- which means in this world, they have almost as much agency as Idaho, though not his incredible power (comparable to that of Anthony Fremont in the famous Jerome Bixby short story/Twilight Zone episode "It's a Good Life", recently covered in my favorite of all the podcasts, Strange Studies of Strange Stories, nee The H.P. Lovecraft Literary Podcast). Among them is poor Madison, now a figure of almost holy reverence but unique peril; anyone who gets too close to her not only pities her sad fate at the jaws of the wolves that attacked her and Idaho in the Before Times, but is also afflicted with paralyzing, mind-destroying sadness.

Tony Burgess, author of Idaho Winter, knowing that all of this is his fault, resolves to set things right with the help of this strange underground (including Madison, whom he somewhat ingeniously finds a way to bring along on their quest). How successful is he in doing so? Knowing that this is a Tony Burgess book, you cannot assume that he will be successful at all, just that you're going to want to see if he is. Or isn't.

The absurdity and insanity of Idaho Winter is only enhanced in audio book form by the choice of narrator, and his choices in bringing the story to us. Tristan Morris gives a prim, Niles Crane quality to the prose that is so at odds with the subject matter that the listener/reader can't help but giggle at the slapstick horrors Burgess unleashes, and handles the many challenges of bringing a book like this to life -- like rendering the muffled voice of a second head that has sprouted from the back of Mrs. Joost, the homicidal crossing guard, a head that is compelled to narrate events in real time like a deranged newscaster -- with imagination and a minimum of fancy production tricks. Read Idaho Winter in print if you prefer, but I highly recommend the audio book, which will take up only three hours or so of your time, for extra fun. And this novel is fun in addition to horrifying and depressing and gross and sad. I mean, it's Tony Burgess.

*The title of which I kept conflating with the more famous Three-Body Problem by Cixin Liu and thus repeatedly convinced myself I'd already read Three Body Problem for a very long time.