It's so big, in fact, that I think a regular single post on the book won't possibly do it justice, nor, in all likelihood, would breaking it into pre-arranged parts or pieces like I did with, say, 2666. So I'm going to do it diary style. However much I read in a day, that's how much I'll cover in that day's post. Maybe this will be cool and fun, maybe not.

So! Ok the last day of this dreadful year of 2023, I'm starting my very first read of Ducks, Newburyport. And away we go!

"When you are all sinew, struggle and solitude, your young – being soft, plump, vulnerable – may remind you of prey."

I was not expecting this to start off from the point of view of a mama cat, but sure, why not? We're treated to the experience of having a litter of kittens utterly depending on one in the first week of their lives, and I couldn't stop thinking of that other, entire novel from the point of view of a cat character, Robert Repino's Mort(e), which starts with the titular hero developing a close relationship with his neighbor's dog. Maybe Morte is these kittens' daddy. Who knows? Why not? This whole book could take part between early chapters of Mort(e), before the ants unleash their uplift virus that makes animals sentient. Wouldn't that be interesting?

But wait, no, is this maybe about a mountain lion or bobcat or something rather than a domestic cat, because the "den" is maybe not metaphorical and mama cat is dreaming about hunting because she actually has to hunt to produce milk? But then how much does this matter, because soon enough we're off on a giant stream-of-consciousness on the part of, I think, a suburban mom but now I don't trust my first impression interpretations at all! And if the whole book continues like this, we'll, I can see where it would be hard to break into pre-planned reading chunks so maybe I've accidentally stumbled across the perfect way to blog this?

By the way, I tried very hard to keep away from reviews or impressions of Ducks, Newburyport, having avoided even the season of the Two Month Review podcast dedicated to it, so I'd know as little as possible about the book, going in.

Our main narrator, whom we learn is indeed the parent of four children if not for sure their mother, feels like a member of my generation but I do encounter an unbridgeable divide between her(?) and me: thoughts come around a few times to the Titanic but this book was published before Oceangate so can I even relate to this character now, who doesn't think of billionaires and orcas when the subject of the Titanic comes up? Lo, how swiftly differences in understanding magnify and ramify, but isn't that why we read and write fiction?

Anyway, I find myself liking her(?) so far, even if she does begin every new thought with "the fact that" like a precocious little kid whom you shouldn't have asked what they learned in school today. I mean, I kind of was that kid, back in the halcyon days of the Nixon administration...

Meanwhile, ok, I'm pretty sure the narrator is a woman, a mother, because I've suddenly got strong Nightbitch vibes from passages like this:

...Leo really has no idea what goes on here all day, the fact that he’d probably flip out if he ever found out what’s really involved in feeding, clothing, housing and shepherding four whole kids, kidherding, the fact that my entire life is now spent catering to their needs and demands, cleaning toilets, filling lunchboxes, labeling all their personal property, shampooing and brushing hair, discussing everything, searching for lost stuff...

Amusingly, my Kindle tells me I have 25 hours and 53 minutes left in this book by the time I reach my fairly certain conclusion that the narrator is female. Which means that no, I haven't even read the jacket copy, which no doubt gives that away, right away. Buckle up!

Questions I already have on Day One of this read:

1. Who is this Stacy the narrator keeps mentioning? My guess right now is that Stacy is the narrator's grown, or at least oldest, daughter, maybe from her first marriage (begun in a silver-grey dress) while maybe the rest of the kids are from her second (blue and white dress)?

2. I originally thought Leo was the narrator's one and only husband but later she(?) mentions an Ethan. Leo is spoken of as someone who she(?) should have trained early on to help with the copious housework but later Ethan is mentioned as having a den for which he should get a pinball machine and hey, I want a den with a pinball machine! Can I have a den with a pinball machine? I would want the Addams Family one like we had at DeKline at Bard in the 90s, how about you? How about Ethan? Would Leo also like a den with a pinball machine?

3. What's up with the kitty in the prologue? I'm reminded now, as I ponder it, the lovely, lyrical passage at the beginning of Ursula K. Leguin's The Lathe of Heaven, in which the author describes a jellyfish "current-borne" and "wave-flung" and which I've always thought of as poor George's first effective dream** and that it turned him into the essentially passive character he is for most of his novel. Is this cat something our narrator is imagining or remembering or using as a lens with which to understand her life? Will she turn into a werecat the way the protagonist of Nightbitch turns into a weredog? Or are they destined to meet, woman(?) and cat, in a culminating scene a thousand pages from now?

4. Am I ever going to see a period/full stop again?

5. Is anyone attempting to translate this novel into other languages? Don't tell me it can't be done; I've read lots of Jose Saramago in English!

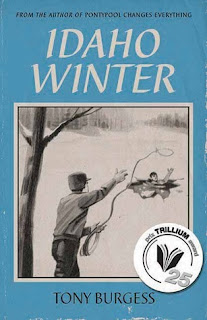

6. The title and cover art promised me ducks. Where are the ducks? There ought to be ducks. Send in the Ducks. And the Newburyport.

*I'm guessing Leo is her husband. But then, I thought the cat in the prologue(?) was a wee domestic cat though I still hold onto the possibility that the cat could still be a housecat with delusions of grandeur.

**Ugh, now whenever I encounter the word "effective" as a modifier of another word, my brain immediately inserts "altruism" and my mind projectile vomits with tremendous force. The 21st Century sucks so hard.

Blogger's note: I'll probably cover more grounds on this in subsequent days, but I had a big ol' pot of gumbo to make for my family's meagre New Year's Eve, which is already over and it's time for this Little Black Duck to go to bed. More tomorrow. And Tomorrow. And Tomorrow. But for now, Duck off!