In this unspecified Hungarian town, one Tünde* Eszter is dissatisfied enough, and, estranged from her eccentric musicologist husband, who already thinks she's a monster, she's certainly feeling under-appreciated.

Be careful when you choose your allies, though.

A long time ago (almost ten years!), back when most of us were still getting our foreign films through snail mail from this cool new company called Netflix,* I finally got my hands on an intriguing film by Bela Tarr called

and fell completely in love. It still haunts me and I've gladly watched bad transfers of it on YouTube a few times since, and know the Vig Mihaly soundtrack all but note for note, but only now am I getting around to reading the novel, László Krasznahorkai's

the film was adapted from.

I said back in 2013 (remember 2013? When we still thought we had the luxury of believing that it would take more than one weird little guy traveling with a taxidermy whale to turn a group of bored people into a rampaging cudgel waving hate mob out to destroy something? But the Hungarians knew better, didn't they? Even back when the film was made [2000]? Maybe because they already had Viktor Orban on their hands in his first term as prime minister? Bela and Laszlo were trying to warn us, you guys!) that this film felt more like a music video than a traditional narrative film, and to this I still hold after a recent re-viewing, but how, then, is it based on a novel?

Speaking one last time about the film: famously it is constructed from 39 long tracking shots and right away I see an affinity between Béla Tarr and László Krasznahorkai in that Krasznahorkai (or at least translator George Szirtes, but I feel like Szirtes would have been discouraged by the publishering team from imposing this on us if it wasn't a trait of the original Hungarian text) indulges in some looooooong sentences, one after the other. Like this one from the prologue, in which an older lady is riding a rickety improvised train full of riff-raff through the outskirts of the town she is already dreading having to walk through to her house in the dark:

That's all one sentence. And I know I'm one to talk, but wow! And it's followed immediately by one just as long and then another almost as long and Vig Mihaly's slightly repetitive but beautiful soundtrack combined with either Tarr's long tracking shots or K's long sentences is kind of... hypnotic? Which is interesting, since this story is largely about how one bad actor can make a whole lot of people do bad things... and suddenly, lulled by many long sentences like this we're brought up short by a relatively short one with shocking and sudden violence: "Down in its depths, around the artesian well, she glimpsed a clotted mass of shadows, a dumb group who, it seemed to her, were silently beating someone."

As I've already said, the novel takes place in a smallish Hungarian city -- actually, my idea of the size of the municipality involved is all out of whack because I come from a town with fewer than 2000 residents and did most of my teenaged hanging out in one with around 500, so my version of a Small Town is much, much smaller than most people's, as is my version of a remote town; Wyoming is famously described as a small town with some long streets -- and our "streets" aren't served by public transportation. Anyway, this unnamed Hungarian town has a train station and a lot of other amenities that I associate with big cities but that I know are more widely and evenly distributed around Europe, but it feels very small in that it is confined chiefly to the area that red herring protagonist and postal carrier János Valuska serves, which is its downtown and whatever residences most closely abut it.

And it's winter, a hard and bleak and unusually cold even for the season winter, in that blah period between Christmas and springtime -- but without any snowfall, which emphasizes the bleakness of it all.

Everybody is bored and listless with a few key exceptions, the main being the aforementioned Tünde Eszter, an incredible busybody even before she was elected president of some kind of women's council that exercises a certain degree of power within the town. She seems to answer only to the mayor, at any rate, and it is a project of hers that has set everything in ponderous and dangerous motion, though it'll be a while before we realize what she has done or its consequences, which will mostly fall on Valuska, though there will be plenty of other victims before the novel is through.

The most notable of these is her poor estranged husband, Gyorgy, a musicologist who until recently taught at the local music academy (see what I mean about how this sometimes sounds like a city of some size? Not only does it boast a symphony orchestra but also a music academy!), until he had a complicated, life-changing revelation while waiting for a piano tuner to finish his job and clear out for the night. It's a weird revelation that I'm not sure I've understood properly, but it seems to boil down to, music/mathematics might be real, as in the relationships between notes/frequencies actually matter, and they aren't just things that we made up?. Thus the

Music of the Spheres is more than just a metaphor.

In the process of having this revelation, Gyorgy also realized that the genetic/viral time bomb in his body (which is the same one that I, your humble blogger, have, as it turns out!) was starting to go off and that this meant he was no longer going to be able to handle life with his monstrous wife and he'd better get her to clear out of their home and his life. Which she surprised him at the time by agreeing to, mostly -- she still insists on doing his laundry, which she passes along to him via Valuska -- but has made it clear in all sorts of creepy and threatening ways that she considers their living apart to be a temporary arrangement.

Alas, she has very recently decided that it's time for that arrangement to end, because the fucking patriarchy insists that if she is going to wield any real power in their world, she is going to need her husband to be the figurehead that appears to be exercising power while she does all the work and makes the actual decisions in obscurity. In this Mrs. Eszter reminds me a lot of Bettina, Harry Joy's bitter and thwarted wife in Peter Carey's Bliss (and Ray Lawrence's sadly underrated film adaptation of that wonderful novel). Her fulfillment requires his suffering, and she looks after herself first, thank you very much.

Meanwhile, her Philip K. Dick character of a husband seems stuck in the Tomb World and, kind of like his wife, can't stop focusing on the kipple that everybody else seems to have (pardon the phrase) tuned out:

"Rubbish. Everywhere he looked the roads and pavements were covered with a seamless, chinkless armour of detritus and this supernaturally glimmering river of waste, trodden into pulp and frozen into a solid mass by the piercing cold, wound away into the distant twilight greyness."

This poor sap is supposed to head up his wife's "movement for moral re-armament?" And if that phrase gives you the willies, well, just wait.

That Mrs. Eszter's initial slogan is "A TIDY YARD, AN ORDERLY HOUSE" is surely a mere detail, right?

Anyway, what Mrs. Eszter has done to prepare for his advent as a leader under her control is... arrange for a small traveling show to come to town, though perhaps the adjective should be something more like "miniscule" since it seems to consist of a single exhibit (though the exhibit itself is large): a taxidermy whale over 50 meters long, being hauled around the countryside in a giant corrugated metal trailer by a standard disreputable carny who charges a small fee for people to climb up into the trailer and look at the whale up close -- a rare opportunity in landlocked Hungary! Indeed, it seems to have attracted a bizarre following of thuggish wanderers who follow it from town to town, on foot, easily done since this thing moves very, very slowly.

Krasznahorkai -- and Tarr -- get a lot of mileage out of this show's slow and ominous entry into town. The truck and trailer take up a lot of room and move very slowly. The rig is so big and so slow that it would surely cause traffic problems by day. Fortunately it's late at night when the thing pulls into town, its entry witnessed chiefly by Valuska as he walks home, slightly drunk, from his usual night at the local inn, which he tried to liven up by rhapsodizing to his drinking... can I call them drinking buddies? Drinking acquaintances, surely, of many years, but buddies? Perhaps not. But more than acquaintances. They've known him and tolerated his eccentricities all of his life. Anyway, he spent the evening drinking a sweet liqueur because he doesn't like the taste of beer or the harder stuff, and rhapsodizing to his fellow drinkers about the wonders of the cosmos and especially of solar eclipses. He wound up getting several of the inn patrons to get unsteadily up from their chairs and act as a living orrery, one guy as the sun, one guy as the moon, one as earth, staggering through their proscribed orbits until the innkeeper finally gets everybody's attention so he can kick them out and close.

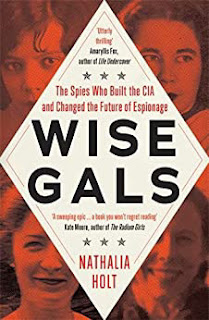

Cue the big rig with the whale, although when Valuska first sees it he doesn't know at all what's inside, just that it's big, though before he's reached home he's seen a bill posted (niftily mimicked for some of The Melancholy of Resistance's more interesting book covers, as I've shown here) announcing the whale and capturing his curiosity. Valuska looks forward to getting to see this whale; he doesn't just love the stars, though they're his favorite. He loves the universe!

But remember the scene the woman walking home from the train station that same night witnessed by the artesian well? And thought were just local drunks acting out? They could have been drunks but they were not local, and their appearance in town coincides with the advent of the whale.

The violence that ensues, in which poor Valuska is caught up and in which unbelievable destruction is wrought on the town, is masterfully depicted without resorting to blow by blow accounts of who does what. It's even more effectively depicted in the film, of course, but Krasnahorkai gave it its first hallucinatory treatment while never letting us lose track of the two most important threads: Mrs. Estzer's quest for power, and Gyorgy's belated realization that Valuska's friendship is actually the most important thing in his life. There are some truly haunting scenes as Valuska seeks shelter and Gyorgy seeks Valuska, never realizing the part that his wife has played in all of this -- because no one does.

Amusingly, this all wraps up with the pages-long metaphor detailing the biochemical breakdown of a human body as it decomposes after death, in which I kept waiting for Qfwfq, the eternal omniscient narrator of another book I'm reading now, Italo Calvino's The Complete Cosmicomics, to show up, either to turn out to be one of the Carbon atoms liberated in the process or to be the decaying body itself. This was nowhere near the point of this coda to the novel, of course, but as I read my way through a collection of translated literature from nations that were once part of the Austro-Hungarian empire in a month I'm calling Radetzky March, I couldn't not think of it, which relieved some of The Melancholy of Resistance's bitterness as it ended with a mocking fascist testimonial to one of its many victims.

Onward with a ragged cheer I go, to representatives of other former bearers of the Hapsburg Yoke. I hope some of the others are a little more cheerful? But one of them is definitely going to be more Robert Musil, so... probably not.

*Damn, I love Hungarian names! Gyorgy's wife is named Tünde, by the way, a name originally derived from that of a fairy in a famous play that I'm going to have to read soon. She is not in the least fairy-like, of course, as her husband ruefully likes to observe -- unless, well, she's got some tough standards she doesn't always bother to communicate to lesser beings, and she's certainly mercurial. Anyway, here's where I confess that when I first watched the movie I was too excited to see Hannah Schygulla in the role that I just assumed "Tünde" must be Hungarian for "aunt" and since Valuska persisted in calling Gyorgy "uncle"...