"What is it?" he asked. "And don't say nothing because you look like you've seen a ghost and we've seen too many fucking ghosts to be scared of them."

Kate Sherrod blogs in prose! Absolutely partial opinions on films, books, television, comics and games that catch my attention. May be timely and current, may not. Ware spoilers.

Monday, May 30, 2022

Zoraida Córdova's THE INHERITANCE OF ORQUÍDEA DIVINA

Sunday, January 30, 2022

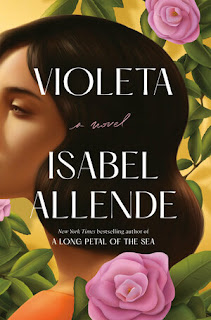

Isabel Allende's VIOLETA (tr by Francis Riddle)

It's not hard to make me cry these days -- one of the many reasons I've pretty much stopped watching television is that I bawl uncontrollably, even at commercials, so we won't even talk about sporting events or scripted dramas like Call the Midwife.* Or, say, The Expanse, which, we all know the last time a book made me cry; it wasn't that long ago, was it?

So it should come as no surprise that I've spent the last few days peering at my ebook reader through a film of tears, because I've been reading Isabel Allende, a writer whom I haven't read since I had to read her debut novel for a class in college, long before my cry-at-everything problem surfaced in my life, but yeah, I cried then, too. So I should have been prepared for Violeta.Sometimes our fates take turns that we don't notice in the moment they occur, but if you live as long as I have they become clear in hindsight. At each crossroads or fork we must decide which direction to take. These decisions may determine the course of the rest of our lives. That's what happened to me the day I recovered Torito's cross.

The passage I quoted above occurs quite late in the novel and wasn't the first bit that elicited the waterworks, but it's the most important to the plot, so I'm going to talk about it and yeah, you guys don't pay attention to the tagline on this blog anymore so spoilers except, of course, this being historical fiction, history itself is the greatest spoiler of them all.

The title character, Violeta, is a member of the same clan readers first encountered in Allende's first novel House of the Spirits(which I read for a class in college when it was still pretty new), whose life spans an entire century in her native land (a never-named Chile but come on, it's obviously Chile) with excursions to the United States and to Europe over the course of an extraordinary life that begins in the Great Depression with her family's fall from upper class splendor to living off the charity of the kindly back-of-beyond family of Violete's governess' lover Teresa, continues through a tepid marriage to a German veterinarian that brings her within a whisker of getting involved in a fictionalized Colonia Dignidad, a scorching love affair with a dashing criminal pilot with ties to all of the right-wing evil that South America and the United States have to offer (and it is he who fathers her two children and madly complicates her life for decades while she is still technically married to the German), a nice one with the guy whom she originally meets when her criminal lover hires him to keep track of their wayward daughter in 1960s Las Vegas, and finally a delightful autumnal relationship with a Norwegian diplomat and bird watcher.

The love of her life, though, as we are told early on, is someone named Camilio, whose actual relationship to her is kept secret until quite late; two other men loom large and protective and helpful in her life in the form of her brother, Jose Antonio, and the Torito mentioned in the passage I quoted above. Her brother shares his business acumen with her early on in life, allowing her to develop a powerful skill set that lets her support herself as an independent woman in a time and place when that was a unicorn; Torito is a family retainer whom she has always known, something of a father figure, not conventionally intelligent or intellecutal and huge, so commonly thought of as developmentally disabled (the novel uses the R word), who comes through for her at a desperate time and pays the ultimate price for it.

I have defined Violeta so far through her relationships with men, but there are also incredible women in her life, starting with her Irish governess, who comes to her as a nanny dressed like a flapper in the 1920s, young and pretty but already damaged by a devastating past as an orphan girl in Ireland but determined not to let that stop her; her relationship with another woman, the aforementioned Teresa, not only governs the early course of Violeta's life as the source of her family's refuge after their fall in the Great Depression, but also involves them all in radical politics from the movement for women's suffrage through the election of Chile's first Socialist president and the sweeping reforms that were utimately his downfall.

In addition to the governess are two extraordinary maiden aunts, a pair of itinerant schoolteachers who train up Violeta to maybe someday join their ranks, a cook who becomes her family's link to the indigenous population in the south of the nation, and so many more. If a character gets a name, they get a full story, relayed in intimate, chatty detail by narrator Violeta, who is recounting the whole of her life and her evolution from spoiled only daughter of a rich family to wayward wife of a German immigrant to conservative, self-supporting savvy businesswoman to radical founder of a social justice organization that looks poised to outlive her -- all for the benefit of her beloved Camilio.

All this means that, yes, Violeta lives through the brutal military dictatorship led by Pinochet. At first she doesn't think it's going to be so bad -- she has thriving businesses, plenty of money, and government contracts that look like they're going to be honored -- and her awakening to the actual nature of the right-wing dictatorship that takes over her country, the finding of a wooden cruxifix she carved as a little girl for her big, strange friend Torito, is sudden, shocking and emotionally wrenching -- and absolutely organic. Allende was great back in the 1980s and has only gotten better, so fluid and natural now that I don't even notice her, which I can also say for translator Francis Riddle.

I mean it as a tremendous compliment to observe that I didn't notice either of them as I was absorbed completely into the story. And crying.

*To name a show that all of the women in my life love passionately and honestly, I don't know how they do it. Every damned episode I've seen has left me sobbing uncontrollably for, like, days? And I have enough to cry about in real life? But there you go. God damn that show.

Wednesday, October 20, 2021

Roberto Bolaño's 2666: The Part About Amalfitano (tr. by Natasha Wimmer)

(Blogger's note: this is Part 2 of a [probably] five-part post about Roberto Bolaño's 2666. Click here to read Part 1, if you haven't already)

This entry is where it's going to be a bit absurd to be devoting a post to each of the five parts, as "The Part About Amalfitano" is a whopping 68 pages long, but Roberto Bolaño packed a lot into those 68 pages of 2666.

We learn right away a thing or two about our hero, that Oscar Amalfitano (a Chilean professor with an Italian name to go with the mysterious German writer with the Italian name) whom the Critics snubbed but whose help and company they accepted in northern Mexico as the closest thing they were going to get to a Native Companion in the David Foster Wallace sense: that he has a daughter, and that the weird book of poems about geometry that was hanging from the clothesline at his house was there for rather more interesting reasons than we might have suspected. Also, he has an entertainingly eccentric ex-wife. And he might be a semi-closeted gay man with a lot of internalized self-loathing about that. Which the Critics kind of suspected, but for the wrong reasons.First, the daughter. Rosa, by the time the Critics come to Santa Teresa, is a teenaged girl who has been raised almost exclusively by her father, who seems to have done a creditable job in that she has grown up into a competent and capable young woman with a healthy social life and a bottomless well of patience to draw on as she gets sucked more and more into the role of housekeeper in her father's book-infested household. Her mother left when she was just a baby, came back once when she was about ten years old, and both times left her without saying good-bye. She has a half-brother, her mother's little son by some man other than Amalfitano, somewhere in the world, probably Europe, whom she seems unlikely ever to meet. And also, because her mother was Spanish, Rosa has a European passport, while her father's is South American, meaning when they travel together they have to go through separate lines at airports' Customs and Immigration areas, resulting in a few slightly traumatic scenes in both of their pasts. Rosa is also, of course, just the right age to be targeted by the serial killer whose existence was only hinted at in "The Part About the Critics" but is started to emerge as a full-blown matter for concern in "The Part About Amalfitano." Gosh, I can't imagine why...

The geometry/poetry book is a tome that turned up in one of Amalfitano's many boxes of books when he moved from Barcelona, where he'd held a faculty position on a contract that ran out right around the time he met an appealing woman professor from the university in Santa Teresa and let her recruit him. He can't account for its existence in his collection at all, has never been to Santiago de Compostela, let alone to its bookstore whose label is on its cover, claims to know next to nothing about the poet who wrote it, one Rafael Dieste, who was an actual person and not a Bolaño creation. As I'll discuss in a moment, Amalfitano, with Bolaño's help, might be obscuring a more personal connection to this poet from us, but for the moment we must simply accept that he has no idea why he owns a copy of Testamento Geometrico (not a real book, but similar to a maybe-real book*). He has no intention of actually reading it, nor can he persuade Rosa to give it a try, so he does what any self-respecting Chilean-sea-bass-out-of-water would do, he uses it to recreate a Marcel Duchamp "Readymade"**, in which a geometry textbook was hung from a clothesline and exposed to the elements. Amalfitano decides to do the same with his unwanted poetry book, and expresses hopes that the book, full of idealizations about abstractions about the world, will learn something about the real world, or perhaps that the wind riffling its pages will learn something about geometry, and thus about the artificial structures it blows around and through in cities like Santa Teresa.

As for the poet, Dieste, while the dates of Dieste's actual life don't really match up, I can't stop thinking about the possibility that Dieste could be the poet with whom Amalfitano's wild thing of a wife, Lola, becomes obsessed to the point of ditching her husband and baby daughter to go off and hatch a screwball plan to break The Poet out of a Spanish mental hospital and begin an itinerant lifestyle with him in France and have his baby. Despite The Poet being gay. Now, since I know nothing at all about Rafael Dieste, I don't know if he was gay or if he spent time in a mental hospital -- it doesn't seem, from a few minutes googling, that either was true of him, but I kept running into articles in Galician and my straight up Spanish is terrible, so I'm not prepared to make a firm statement about what I found. HOWEVER...

If Dieste and The Poet are the same person, that would be one reason right there for Amalfitano to have a subconscious hostility toward Dieste's book, of a kind that would let him justify mistreating it as an homage to Duchamp***. His wife's obsession with The Poet ruined his family, after all.

BUT...

Amalfitano may have a hand in all this himself. For while Lola insists that she met The Poet long ago and even had a one-night-stand with him at a party hosted by "the gay philosopher" with whom The Poet then lived (and which the philosopher and two other friends allegedly watched), Amalfitano's version of the backstory to her obsession is very different: she had never heard of The Poet before Amalfitano introduced her to The Poet's work. Lola is a free spirit, to say the least, and very liberal with her embroideries on the truth, and is perfectly capable not only of appropriating another's story as her own but on embellishing the hell out of it, which then brings up the question: since the alleged sexual encounter with The Poet can't actually have happened with Lola, could it have actually been Amalfitano's story originally? One of which he is deeply ashamed, as his extensive internal dialogue (we'll get to that) with himself, laden as it is with expressions of internalized homophobia, strongly suggests?

Did I mention there's a lot packed into these 68 pages? There's a lot.

But so, some more about Lola. We get her whole back story before we've learned anything, really, about Amalfitano or his daughter, via a series of rambling and unfiltered letters she sent to Amalfitano during her rampages through Spain and France. She is a deeply unreliable narrator so it's impossible to tell what, if anything, is true, but these letters are some of the most entertaining storytelling in all of 2666. Lola has no shame, nor much sense of self-regard; she doesn't mind looking filthy or being used as a prostitute or sleeping rough in a cemetery, will tell any lie she needs to in order to achieve a goal and comes up with some whoppers. I would read a whole novel about Lola. But I'll take what I can get.

Later on, after Lola has sashayed into the sunset and Rosa has grown into a teenager, Amalfitano has developed some odd habits that may well grow out of his internal issues with regards to The Poet, whether or not The Poet is Dieste: he's started making strange geometric doodles in which he tries to visually map the relationshps between various philosophers and other famous thinkers, ranging from Plato and Aristotle to Jacques Lacan and Doris Lessing and including both Harold and Allan Bloom. And he's started hearing a voice in his head that claims to be his long-dead grandfather, but later admits merely to being his father. And his head-father is obsessed with boxing (which will be a big part of the next book "The Part About Fate") with the idea that all Chileans are homosexuals (except dad mostly says "faggot" because dads gotta dad) and that he, Amalfitano probably is one, too, and dad's feelings about that possible fact are conflicted. Twice in this section someone muses about the idea that madness is contagious; with these aural hallucinations it seems that Amalfitano has either caught it from his wife, or might have been the Patient Zero in this relationship. This section, after all, starts with him asking himself a few rhetorical questions about why the hell he's even in Santa Teresa.

Meanwhile and elsewhere in Santa Teresa, they keep finding dead bodies of teenaged girls and young women in vacant lots near the edge of the desert, because 2666 gotta 2666. And while Rosa is mature for her age and very capable, she sure tends to get home late a lot...

One last bit of interest, here, though it may be nothing. We get to see a bit of the true relationship between Amalfitano and the son of the Dean of the university, Miguel Antonio Guerra -- a rather unpleasant young man with a habit of going to rough clubs in the city and pretending to be gay, the better to pick fights, and whom the Critics in "The Part About the Critics" at first suspected of being Amalfitano's highly inappropriate paramour. Guerra seems intended to be an early red herring candidate for being The Killer in that he is the only person we've encountered for who actively seeks out violence and goes armed.****

And... I still don't know what to make of Amalfitano's Part-ending dream in which Boris Yeltsin "the last of the Communist philosphers" (would Yeltsin, who presided over the fire sale of state assets to a bunch of would-be oligarchs that allowed them to become actual oligarchs, agree to this title, I wonder?) reveals to him the true economic formula of our times, which is apparently "supply+demand+magic" where magic is probably actually just advertising, or, as Amalfitano reckons magic to be "epic and also sex and Dionysian mists and play," which sounds like advertising to me and now I'm thinking once again about one of my favorite films of all time, based on a novel by one of my favorite writers, the blisteringly awesome Generation P***** (which, actually, prominently features one Boris Yeltsin in its phantasmagoria) and I can think of no better way to end this post and this section of 2666 than by embedding the film in its entirety here, just to be stupid, but really, you should just fire up YouTube on an actual television and bask in its glory properly (I got to see it on the big screen and chat with its director for a bit afterwards because once upon a time I got to do awesome things like go to the Toronto International Film Festival). Go forth and marvel at the film that predicted Deep Fakes by more than a decade, my lovelies!

And then watch this space for more 2666, coming very soon.

*As in it's hard to tell. One can google Dieste's Nuevo Tratado del Paralelismo, and get a few hits that even show a charmingly worn copy in a photograph, complete with a table of contents, but since most of the sites that link to it are actually dedicated to 2666, I'm not sure if it's a real book either. I mean, I myself own a hoodie that celebrates my "visit" to Oakland, CA's entirely fictional Telegraph Records from Michael Chabon's Telegraph Avenue, after all. But clearly, Rafael Dieste sounds like an interesting man and an interesting poet I look forward to learning more about someday.

**Kind of a spiritual ancestor to Yoko Ono's "Instructions" maybe?

***Who, by the way, entitled his work exposing a geometry book to the elements the Unhappy Readymade, and by the way, Duchamp didn't actually do this to a book but told his sister to do it. She did, and later made a painting of the book after it had been exposed. Only this painting of the original project survives now.

****Of course, I think we've already had a glimpse of the person who will be determined is the most likely suspect in the killings, in another bar, in "The Part About the Critics", where Espinoza drinks alone the day they've dropped off Liz. All Espinoza notices about him is that he is very tall, tall like Archimboldi is said to be just exceedingly ridiculously tall, but this man seems too young to be Archimboldi. Is this [REDACTED]? As usual, I don't effing remember if this is a dot that gets connected or not.

*****Based on Victor Pelevin's terrific and criminally underappreicated novel Homo Zapiens. It's a very faithful adapatation.

Friday, October 15, 2021

Roberto Bolaño's 2666: THE PART ABOUT THE CRITICS (tr by Natasha Wimmer)

The oblique drops of rain slid down the blades of grass in the park, but it would have made no difference if they had slid up. Then the oblique (drops) turned around (drops), swallowed up by the earth underpinning the grass, and the grass and the earth seemed to talk, no, not talk, argue their incomprehensible words like crystallized spiderwebs or the briefest crystallized vomitings, a barely audible rustling, as if instead of drinking tea that afternoon Norton had drunk a steaming cup of peyote.*