had a lovely idea for wrapping up what has honestly been a pretty wretched year for those of us who don't coat our faces with weird orange makeup every morning. I had originally been persuaded by my Own Dear Personal Mom to do a favorite books of 2024 post when Ben shared

on Mastodon (aka the best alternative to the cesspool that once was our beloved bird site). What a fantastic idea! After all, even I occasionally do things besides reading.

But let's be honest: this is mostly going to be about reading. Because I've given up most other forms of recreation for various reasons, many of them medical but many because I realized a few years ago that I'm well past the likely midway point in my lifespan and likely do not have enough time left, even if I gave up sleeping (which I already do very little of), to read everything on my ever-growing To Be Read list.

But anyway, enough preamble. On with what I liked from this year.

Television

What? A big long paragraph about how all I want to do is read and I'm starting with TV? Something I resentfully sit through while still sneaking a page or two, just for the sake of spending "quality time" with my family? Yes. The Imp of the Perverse built a mansion on my shoulder and is very hard to coax out of it. Almost as if it has been sentenced to house arrest there or something! Which, you'll see what I did there in a moment.

Showtime's excellent adaptation of

Amor Towles' wonderful novel was the only TV show I watched this year that I hadn't already seen before (the only other thing I watched, besides pretending to pay attention to some Buffalo Bills games with my mom and sister, was the BBC's 2000 adaptation of Mervyn Peake's

Gormenghast trilogy) and I just watched it over the holidays with my family and I loved it. Ewan McGregor was in no way who I imagined as Alexander Rostov when I originally listened to the excellent audio edition of the novel narrated by Nicholas Guy Smith; as is usually the case when I imagine a Russian male character, my mind casts

Anatoly Solynitsin in the role. But McGregor was great, as was his gorgeous and intelligent wife Mary Elizabeth Winstead as Anna Urbanovna and the young women who played Nina and Sofia. This story of a Russian count who escapes the fate of most of his peers in the Russian Revolution via a misattributed poem that convinced the new regime he would be useful to them if kept prisoner in Moscow's famous Metropole Hotel could easily have been dominated by the production design but the show's creators wisely focused very tightly on Towles' amazing cast of characters and their stories. The show is worthy of the novel, and of all the hype it has received.

Music

I'm a middle aged fuddy duddy who has tried to keep myself open to new music, but I'm afraid this year was very much dominated for me by "legacy acts" releasing brand new albums that kept true to why I originally loved them but don't sound like they came through a time portal from the eras in which these acts first gained fame.

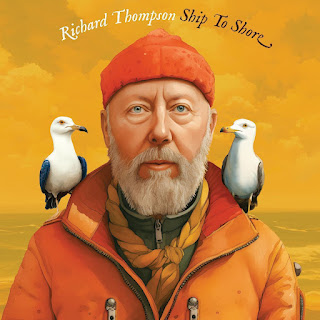

Richard Thompson - SHIP TO SHORE

I've loved Richard Thompson since my partner on our very amateurish college radio show first introduced me to Thompson's RUMOR & SIGH back in 1991. I kept up with his new output and happily explored his back catalog with Linda Thompson, Fairport Convention, etc and he's never once bored me. So color me not surprised that his 2024 output is still great. As the cover art conveys, the album has a very nautical feel. It never descends into just "Richard does sea shanties" though that would be fine. Thompson explores many themes that have little to do with the sea along with those that do, balancing the jaunty nautical stuff with his traditionally atmospheric guitar work and his unique and shiver-inducing voice.* My favorite track on here is "Singapore Sadie" but there isn't a skippable cut on here.

John Cale is one of my favorite musicians of all time. The Velvet Underground without him feels incomplete; his solo work is spectacular and varied and he has impeccable taste in collaborators (his albums with Brian Eno, for example, are exceptional) as he demonstrated just last year with his album MERCY, which is how I discovered one of my new favorite singers, Weyes Blood. MERCY

is so good that I took it as a capstone to an amazing career and was grateful to have it, but Cale isn't done yet. POPTICAL ILLUSION is loaded with absolute bangers that I can't stop listening to, especially "Shark-Shark" (which, check out this

bonkers music video) and what I insist is a brand new classic, "How We See the Light." This. Is. Pop.

Laurie Anderson's art is always an event in my world, and her 2024 concept album dedicated to the story of Amelia Earhart is an exceptional example of how affecting her work can be. Even if you set aside her incredible cast of collaborators, the atmosphere of mystery, wonder, adventure and tragedy she conjures out of ordinary instruments and her deep and meditative voice as she narrates her version of Earhart's experiences is absolutely riveting. I'm guilty a lot of the time of using music as a secondary experience -- I blast really complicated prog rock as pain relief, filling my mind with other signals to block the constant neural spam my chronic illnesses constantly harass me with, and I also read a lot while playing music for similar reasons -- but stuff like Amelia occupies me entirely. And it's educational, too!

The Cure - SONGS FOR A LOST WORLD

I mean, you knew this was going to be on here, right? I'm a white Gen Xer from the United States. The Cure was my everything for the 1980s and 1990s.** And as everybody knows, they came into 2024 with an album destined to own it. I'm not going to spend a lot of time on this. The entire Internet is raving about this album. For good reason.

I swear I'm not putting this here just to lay claim to a tiny sliver of hipness or prove that I actually do listen to music that comes from this century, but of course that's the message this really sends, isn't it? I only know of this album because Jordan Holmes, co-host of the Knowledge Fight podcast, mentioned this album as his "bright spot" on an episode -- which is how I've found a lot of "new to me" acts in recent years, including Godspeed! You Black Emperor and Helado Negro, to name two others.*** And yes, a member of G!YBE is in this ensemble. Anyway, this is just great, moody, atmospheric and noisy music that combines a wintry bleakness with environmental sounds, heavy distortion and a painful beauty that stays with me long after the last sounds of "White Phosphorus" fade out.

Books

Ok, I mostly write about books on this blog, and I only write about books that I really really love and that I either think haven't gotten enough attention from the general reading public or I'm obligated to write about in exchange for an advance copy (a habit I'm trying to break but having a hard time with), so really, if you want to know what books I loved in 2024 you could just read my 2024 entries and call it good, but I did read some other excellent books that I didn't write about on here either because I was too ill at the time or because I thought they were getting plenty of coverage elsewhere. So that's what I'm going to focus on here.

CAHOKIA JAZZ was on a few "most anticipated" and "best of early 2024" type lists but then sort of disappeared from discussions about what was an exceptional year for new books. I'd really hate to see this get lost in the shuffle because it is hands down my favorite book that was published this year. I like a good alternate history milieu and CAHOKIA JAZZ has a great one: It's the Roaring 20s in North America, but it's a North America in which the indigenous population largely survived the germ warfare imported by Europeans and went on to flourish, standing up to enough of the waves of settlement to establish urban centers like the city-state of Cahokia, and maintain a melange of Native culture while still adapting with the technological developments and other historical currents of the 20th century -- and welcoming other races and ethnicities. The world thus established is rich and convincing and a spectacular setting in which Francis Spufford enacts a classic crime noir plot that could hold its own against classics like Chinatown. Except instead of clueless white boy Jake Gittes, though, we get Joe Barrow, an accomplished Black jazz pianist who is also a detective on Cahokia's city police force. The grisly, possibly ritualized murder case he catches, in a city where an Aztec pyramid occasionally hosts human sacrifices, turns out to have huge implications for the city-state as a whole. I'd love to see this made into a prestige miniseries. It could be a season of Fargo. Don't skip this one.

Again, I'm one tiny voice in a global chorus of praise. It's a bestseller. It won the National Book Award for fiction. It should have won the Booker Prize. It retells a classic and makes it better and richer. You've probably already read it and loved it. So did I.

I've come to love Alan Moore's prose fiction as much as I do his graphic novels, comics and magazines (yes, I have a stack of early issues of Dodgem Logic and no, I'm not ready to share them with anybody yet), so I eagerly awaited this first novel in his new Long London series that is projected to be a quartet. His most expressly magical work since, say, Promethea, THE GREAT WHEN establishes a dual London slightly remeniscent of China Mieville's THE CITY AND THE CITY but Moore's other London that is contiguous-but-separate from the London we know is utterly bizarre and one hundred percent magical. Or rather, magickal, because this sphere owes more to the likes of Alastair Crowley and Austin Osman Spare than to Gandalf or Dumbledore.

Our hero is a lowly teen who rejoices in the utterly batshit name of Dennis Knuckeyard, who is only surviving post-WWII London through the grudging good graces of Coffin Ada, a second-hand bookshop owner who employs him and let's him live in a room in the flat above the store where she smokes, drinks and knows things. It's a mostly miserable life for Dennis and looks to be made only worse when a mysterious book that shouldn't exist turns up in some new inventory he's been sent to fetch. His adventures in both Londons are bizarre, creepy, fascinating and occasionally tug at the heart, if one still has one. And Coffin Ada is even more magnificent than she sounds.

Audio Dramas & Podcasts

This "found audio" drama in which a broadcaster, who just might be the last human alive on earth after a weird comet's disastrous fly-by, tries to reach out to his missing friend, is also a cool exploration of many alternate earths. Does that make it an anthology series? Kind of.

The comet, in addition to disrupting ordinary life on what I *think* is meant to be our good old ordinary planet Earth but might not be, also has somehow thinned the boundaries between different universes just enough for our broadcaster to receive bursts of radio signals from alternate Earths that all slowly seem to be succumbing to some kind of slow invasion. Our man has started recording these intercepted transmissions and shares curated segments of them as he tries to reach a friend? lover? mentor? relative? whom he believes might still be out there and listening and willing to help figure out what the hell is going on.

Meanwhile we learn of the existence of worlds in which the entire world is an oligarchy still firmly in control of historic dynasties like the Hapsburgs, who routinely enact elaborate assassination plots against one another; in which Christmastime is known only as The Holiday and involves the military mobilization of a child army known as The Naughty to defend the U.S.' northern border from the annual incursion of an eldritch horror that says "ho ho ho"; and, my favorite episode, in which large language models have been allowed to take over entertainment, municipal and emergency services and pretty much everything else, with entertainingly horrible consequences. I'm still waiting for my Paper Street Psychics tour tee shirt.

The show has a large, diverse and ever growing cast of terrific voice actors and singers to play out the collection of snippets of news broadcasts, advertising and recorded proceedings of the government and corporate bodies that make all of these worlds the bizarre, tragic, fascinating and occasionally funny ones they are, while the frame narrative maintains the air of tension and mystery that makes all of this cohere. I've listened to every episode multiple times and I'm still discovering little details in this lovingly crafted weirdness.

I have to really, really love a show to put up with I Heart Media's terrible, terrible advertising, so Molly Conger's fascinating little show had a huge strike against it from the start. And I still sometimes let the new episodes pile up on my podcatcher just because I can't face the awfulness, which, the subject matter is bad enough! But Conger is such a throrough researcher, a candid and self-reflective presenter, and a pleasant and thoughtful personality that Weird Little Guys has become can't-miss listening for me. It just sometimes takes me a few days to steel myself to listen.

Sort of a companion piece to the famous Behind the Bastards, Conger goes small where Robert Evans goes big. She's interested in the lesser known but often just as awful people without whom most of the big bads Evans covers would be much less damaging and dangerous. Conger digs deeply into the backgrounds of the kind of guys who haven't yet made headlines, or have only made very niche headlines for things like burning crosses on other people's property or building pipe bombs for terror projects or creating small but terrible media ecosystems that celebrate mass murderers and urge viewers and listeners to join their ranks and become terror "saints" by planning and executing their own attacks on the unsuspecting public. She's the kind of woman who knows her way around a courtroom and a court filing hundreds of agonizingly dull pages long, and has a true storyteller's instinct for the illustrative details and anecdotes that bring these weird little guys to life and remind us that they live among us and maybe, just maybe, we can prevent one or two of them from going postal on us with a little more kindness and empathy? Maybe? But probably not. By the time they're on Conger's radar, we probably need to duck and cover on sight.

Hosted by two "noided" lawyers podcasting under the pseudonyms of Dick (as in Cheney) and Don (as in Rumsfeld), this show is as weird and disturbing as its title suggests. The general premise of the show is that the much-imagined Fourth Reich (as in the successor to Hitler's Third) is not a thing of the future but of the past and present, and Dick and Don are here to dig out from under decades of propaganda and obfuscation as many clues as they can to prove that the Fourth Reich is an almost seamless continuation of the Third and is better known to us as the international corporate regime that is what really governs the so-called Free World. It's a notion that seems far-fetched and overly paranoid to many, even today, but this pair has a lot of information on their side and are both, as one might expect, very good not only at constructing complex arguments but at effectively communicating them as well.

So far, the gents are focusing on making their case through the lens of the life and career of our 38th President of the United States, Gerald R. Ford. You know, the one nobody outside of the state of Michigan ever got to cast a vote for until he was running for re-election as POTUS and got beat by the late, much lamented, Jimmy Carter. Ford had a much more interesting life than I had ever imagined, as did his wife Betty, who is much more than just a name on rehab chain. While Ford was the first president I was old enough to know my name (just barely!), I knew next to nothing about him except that he'd pardoned Nixon. I now know that this is one of the less interesting facts about the guy.

The show -- which also boasts a killer playlist of interstitial music skillfully deployed to drive home various points -- is currently taking a bit of a detour into a deep, deep dive into the Warren Commission and the men who served on it, one of whom was one Gerald Ford. It gets a bit out there at times but it's never not interesting and, like I said, it's full of facts that I have encountered nowhere else except maybe in Gravity's Rainbow.

There's more, and doubtless stuff I'm forgetting, but it's already 15 days into 2025 and I'm tired. BUT, is there something you think I missed? Let me know over on

Mastodon!

*The first song of his that I ever heard was "Psycho Street" and so I always feel echoes of that in his voice.

**I'm one of those weirdos who prefers KISS ME, KISS ME, KISS ME to DISINTEGRATION, by the way.

***Both of whom also released new albums this year, by the way. They're great, but I'm trying to keep this listing on the short side.