In the case of Wise Gals, the biggest revelation (besides the incredible stories of the titular gals) was that a World War II battle had taken place on American soil, just six months after Pearl Harbor, except kind of six months plus one year after Pearl Harbor because it took the U.S. a long time to land troops to engage the Japanese who had invaded and taken the Aleutian island of Attu, part of the then territory and now state of Alaska.

So of course I'm going to have to read all about that pretty soon because Wikipedia won't do when you're... me. I've already located a book about it in my local public library!

Also, Gloria Steinem worked for the CIA for a hot ten minutes or so in the early 1960s! "In my experience," she said later, "the agency was completely different from its image; it was liberal, nonviolent and honorable."

Ok, Boomer.

Anyway, Wise Gals is a fantastic book about the lives and unsung careers of yet another group of amazing women -- one of whom, Jane Burrell, was the first CIA agent ever to die in the field -- who quietly changed the world despite all the garbage that patriarchy kept shoving at them. In this case, the women were instrumental and fundamental to the development of the United States' intelligence services during World War II and the early stages of the Cold War. Like the ladies of Hidden Figures and Holt's own Rise of the Rocket Girls (which I haven't read yet but now very much want to), these women's names should be as well known as their male counterparts but aren't. At least not yet.

The women whose stories are encompassed in this book were not only there at the founding of the CIA; Holt directly ties their work to the agency's development from a "male, pale and Yale" network of pseudo-aristocratic amateur spies to the sophisticated, data-hoovering, technologically advanced power it is today.

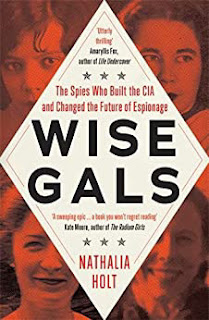

By the way, look how much cooler the UK cover for this book is. The US edition uses a generic model they've given a vaguely 40s hairstyle and some dark lipstick and then cut off the top of her head. In the UK they got to see four of the actual women's faces. I had a terrible time on the internet trying to identify who is in which photo, but I'm sure that they are four of these five: Jane Burrell, Adelaide Hawkins, Elizabeth Sudmeier, Eloise Page, and Dr. Mary Hutchinson. My point is that it wasn't a single unknown woman who did all of the amazing deeds described herein; they were actual, individual human beings with families and interests and personalities and skill sets uniquely theirs. Do better, US publishers.

But I mean, wow, these were some extraordinary people. Burrell, for instance, had to work side by side with ex-Nazis (supposedly, but not always completely, "turned" towards the end of World War II) to expose post-war Nazi plots like giant art thieving and currency counterfeiting schemes, to say nothing of war criminals' escape from justice by disappearing into new identities in new countries. Often her collaborators turned out to be every bit as bad as the people they helped her expose, meaning she spent years in serious danger. What finally got her, though -- she was the first CIA officer killed in the field -- was a plane crash in Europe, cutting short a promising but already distinguished career.

Adelaide Hawkins, not content with a distinguished service record from the war in part because she was supporting and raising three children (she divorced her deadbeat husband right after the war), became one of the first members of the Central Intelligence Agency immediately on its founding and, among other achievements, headed up the team that developed the microdot camera -- an iconic bit of spy kit if there ever was one.

Meanwhile, Eloise Page was, as another OG CIA operative, a leading voice in the campaign to get the rest of the U.S. government to understand that an innocuous seeming calcium processing plant in East Germany was making material for a Soviet nuclear weapons program that was much farther along than technical advisors (who hadn't factored in short cuts like spying in assessing how long before the USSR had The Bomb) were telling it. When she and her colleagues were largely ignored, she helped organize a mission to sabotage the calcium plant -- but by the time the US and British bosses had agreed to put it in motion it was too late.

And history might have been very different if General Douglas MacArthur had paid attention to the hard work of Dr. Mary Hutchison and her colleagues at the CIA's Tokyo station in 1950. She'd only warned everybody authorized to read her stuff that North Korea was getting ready to invade South Korea -- long before some 200,000 Chinese troops massed at the border to lend Kim Il-Sung a hand. Page followed up this feat of sounding the alarms and being ignored by warning her superiors months ahead of time that the Soviets were very close to launching Sputnik, the world's first artificial satellite. You know, the one that took us completely by "surprise."

Some of us were more surprised than others. The Looming Tower*, anyone?

Then there's Elizabeth Sudmeier, who brought our country the first credible intelligence about the world's first mass-produced supersonic aircraft the infamous Soviet MiG-19 fighter plane, which she got via gossip at the Baghdad dressmaker's shop among the well-placed hijab-wearing ladies she had carefully cultivated there. Nobody else in the Near East division could have accomplished this because nobody else was a patient, friendly and engaging young woman -- who genuinely enjoyed spending time there and appreciated the hand-tailored wardrobe her activity allowed her slowly to build. She stayed behind in Baghdad after a fundamentalist coup killed off Iraq's royal family and sent the rest of the CIA's personnel on various frantic escape routes and managed to maintain most of the U.S.'s spy network there until it was (sort of) safe for everyone else to come back. And we won't even talk about her role in the Gary Powers/U-2 affair because you're going to read this book. Right?

Sudmeier's experiences having to leave Iraq after a mole in Washington D.C. blew her cover got me thinking, of course, about Valerie Plame. I wondered about Plame's time as a woman in the CIA in the 1990s and beyond -- and then I learned she has not only written (with a ghost writer) the expected memoir, but also a couple of spy novels! Gonna have to have a look at those one of these days.

Egads, there is still so much I don't know. Which is why I keep on reading...

*And, as Holt takes pains to point out in the summing up of this book, the Wise Gals walked across Europe and the Near and Far East in Ferragamo pumps so the ladies of Alec Station who kept tabs on Osama bin Laden et al could analyze truckloads of data in more sensible shoes, as it were.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Sorry about the CAPTCHA, guys, but without it I was getting 4-5 comment spams an hour.